Boko Haram, Nigerian question and Obadare’s warning

I have known Dr Ebenezer Obadare for many years. I knew him first as a journalist at The News in Lagos, and again when he returned to Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, in 1995 after leaving The News stable. It was a delight engaging him and friends, Professor Chijioke Uwasomba and Yomi Gidado, all budding academics at the time. I have watched his growth as a scholar from afar. I have also watched his phenomenal rise as a public intellectual who never shies away from difficult national questions.

His recent intervention before the U.S. House Appropriations Committee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee is another example of his courage. It is also a warning. It asks Nigeria to confront Boko Haram, Sharia politics, Hisbah police and the crisis of identity at the heart of the northern region. It tells us that the Nigerian question remains unfinished and dangerous. And it tells us that time is running out. Obadare spoke with clarity. He did not drift into abstraction. He took on Boko Haram directly. He called it the deadliest threat confronting the Nigerian state. This is right. The insurgency has torn apart towns and villages. It has erased lives, broken families, left citizens in fear and exposed the fragility of the Nigerian state. It is also reshaping daily life in the North East in violent ways.

His description of Boko Haram is not sentimental. It is clear and firm. It identifies the group as a jihadist movement committed to overthrowing Nigeria and replacing it with a caliphate. Boko Haram has pursued this goal for more than a decade, while bombing schools, raiding markets, abducting children and attacking Christian and Muslim communities. It has wiped out local authority in vast rural tracts. He reminded his audience that any solution that does not degrade and eliminate Boko Haram is a non-starter. This is a serious claim. It is also the truth. Nigeria cannot rebuild its economy or secure its borders if a warlord faction controls territory.

Nigeria cannot protect constitutional rights when an armed sect decides who lives or dies. Nigeria cannot preserve religious liberty when an extremist group imposes doctrine through terror. He went further. He suggested an international strategy that includes incentives and pressure. He pointed to the impact of the Country of Particular Concern designation. He also noted President Trump’s threat of unilateral military action. He argued that these actions forced the Nigerian government to respond. He suggested that Washington must keep up the pressure.

This argument deserves serious attention. It is grounded in a long history of foreign policy. External pressure has shaped domestic responses in many conflict zones. Scholars like Alex de Waal have shown this pattern in Sudan. Paul Collier has discussed it in fragile states. Incentives work. Pressure works. States respond when their survival is tied to diplomatic consequences. Nigeria is no exception. When placed under scrutiny, Nigerian leaders often react.

When confronted with political risk, they take action. The threat of sanctions and the fear of strategic isolation move them, as the Senate President, Godswill Akpabio suggested during the recent confirmation hearing of General Christopher Musa. “Trump is on our neck”, he expressed. Obadare’s claim that the Nigerian authorities are not impervious to incentives is thus correct. We saw this pattern when the United States pressured Nigeria over human trafficking. We saw it when global outrage pushed the government to act after the Chibok abductions. We also saw it when military partners questioned the capacity of the Nigerian military. Pressure-triggered reforms, even if they were partial.

Obadare’s argument became more controversial when he addressed Sharia law in the twelve northern states. He calls for it to be made unconstitutional. He also called for the disbanding of Hisbah groups across northern Nigeria. This is a bold recommendation. It is also a necessary one. The presence of Sharia courts and Hisbah police raises deep constitutional questions. Sharia law in criminal matters violates the secular foundation of the Nigerian state. Hisbah police forces operate outside the federal policing structure. They enforce moral rules that apply to people who do not share the Islamic faith. They create fear among minorities. They mask the line between state power and religious authority.

He sees the link between this system and the growth of extremism. He does not claim that Sharia law produces Boko Haram. He claims that Sharia law and Hisbah structures create an environment where extremist ideas can flourish. This is a serious point. It must be examined carefully. As a constitutional law scholar who has spent three decades engaging with the tensions between law, religion, and state power, I see in these institutions a quiet erosion of the secular foundation upon which the Nigerian Republic stands. They represent not merely parallel structures of justice and enforcement, but a reordering of authority in ways that obscure the line between faith and public power.

The obscure ought to trouble anyone committed to a plural society governed by a single constitutional order. My concern deepens when Sharia criminal law is applied in ways that reach beyond Muslim believers. The Nigerian Constitution does not contemplate the criminalisation of morality under a faith-based legal regime, nor does it permit state-sanctioned coercion in the name of religion. Yet, in reality, Hisbah forces routinely enforce behavioural codes on citizens who do not subscribe to Islamic doctrine. This produces fear among minorities, fosters unequal citizenship, and cultivates a type of social hierarchy that should have no place in a republican democracy.

For me, this is not an abstract legal worry; it is a lived contradiction that threatens national cohesion. I also see a troubling continuum between these state-backed religious structures and the broader ecosystem in which extremist ideas find room to grow. I do not argue that Sharia law created Boko Haram; such a claim would distort history. But I insist that the coexistence of religious policing, moral surveillance, and faith-based criminal law creates an enabling environment that normalises the intrusion of religious authority into public life and weakens resistance to more radical ideological incursions. When a state tolerates, funds, or collaborates with institutions that elevate religious identity above constitutional citizenship, it inadvertently widens the space in which extremism can flourish. This is a serious point, and it must be confronted with intellectual honesty.

Scholars who study the intersection of religion and constitutional governance in Nigeria have long warned that the adoption of Sharia criminal law in twelve northern states represents a cultural assertion and constitutes a structural departure from the secular architecture of the 1999 Constitution. Constitutional theorists such as the late Professor Ben Nwabueze argue that Nigeria’s federal system presupposes a single, unified criminal jurisdiction under federal supremacy.

From this perspective, the introduction of parallel criminal norms based on religious doctrine weakens the coherence of the state. Other scholars, including Rotimi Suberu and Sam Amadi, frame the issue as one of citizenship: when the law fragments along religious lines, the idea of equal citizenship is compromised, and the state becomes vulnerable to sectarian interpretations of justice. Human rights scholars add another layer to the debate. They contend that the implementation of Sharia criminal law violates Nigeria’s international obligations under treaties that guarantee freedom of religion, equality before the law, and due process. From their standpoint, the problem is not simply the existence of Sharia courts, but the normative assumption that theocratic values can define public order. This assumption, they argue, fosters exclusion and weakens the nation’s commitment to universal rights.

Scholars in this school often point to the public flogging of youths, death sentences for alleged apostasy, and gender-discriminatory evidentiary rules as evidence that constitutional secularism is not merely being stretched, but it is being rewritten in practice.

There is also a robust sociological perspective advanced by some academics. Their work does not deny the cultural legitimacy of Islamic law in predominantly Muslim areas. Instead, it highlights the political instrumentalisation of Sharia since 1999, especially by state governors seeking legitimacy in moments of crisis. In this reading, the reintroduction of Sharia criminal codes was less about faith and more about politics; a populist strategy that transformed religious sentiment into a tool of statecraft. This political appropriation, scholars argue, created a landscape in which religious identity became a tool of governance, with consequences that continue to shape northern Nigeria’s security dynamics.

However, I find Obadare’s recommendation that the United States should pressure Nigeria to dismantle Sharia structures provocative. It raises diplomatic questions. It raises questions on sovereignty. It raises political questions. However, these questions become almost secondary when viewed through the lens of the “unable and unwilling” doctrine in international law, which is a standard used in international law to justify intervention or the use of force in another state when that state cannot or will not prevent its territory from being used to launch attacks against others. It recognises that sovereignty is not absolute.

When a state lacks the capacity to stop armed groups operating within its borders, or when it deliberately chooses not to act, other states may have a legal basis to respond to neutralise the threat. This principle has been invoked in counterterrorism and humanitarian contexts. It emphasises responsibility: a state cannot hide behind its borders while its territory is exploited to harm others. The doctrine is particularly relevant in situations involving transnational terrorist groups, such as Boko Haram in Nigeria, where the local government may lack resources or political will to address the threat effectively. It bridges the gap between respecting sovereignty and ensuring security for affected populations.

But the application of the pressure is not without precedent. International pressure has shaped constitutional reform in many countries. Kenya’s 2010 constitution was influenced by donor pressure. Liberia’s post-war reforms were shaped by external actors. Rwanda’s transformation after the genocide was shaped by strict international conditionalities. Nigeria is not new to this type of engagement. It has accepted global pressure on issues like corruption, policing, and human rights. It has accepted pressure on HIV interventions. It has accepted pressure on human trafficking. It can accept pressure on constitutional questions when those questions relate to national security.

The deeper issue is whether dismantling Sharia structures will weaken Boko Haram. The answer is not direct. Boko Haram will not surrender because Hisbah police are disbanded. Boko Haram will not renounce violence because Sharia law is abolished. But extremist groups thrive on contradictions. They exploit the grey areas created by political Islam. They use Sharia structures as proof that Nigeria is an Islamic state in waiting. They use the moral policing of Hisbah to justify their stricter vision. They claim that the state is already drifting toward their ideology. Removing these contradictions deprives them of rhetorical ammunition. It also deprives them of structural openings. It strengthens the constitutional foundation. It protects minorities. It affirms that citizenship is not secondary to religious identity.

There is also a deeper lesson in Obadare’s argument. Boko Haram is not only a military problem. It is a problem of identity. It is a problem of governance. It is a problem of legitimacy. Extremism grows when citizens lose faith in the state. Extremism grows when the state loses moral authority. Extremism grows when public institutions collapse. The Nigerian state has lost trust in many regions. Citizens do not believe the government can protect them. They do not believe the courts can deliver justice. They do not believe the police can secure their communities. They do not believe political leaders care about their suffering. Boko Haram exploits the trust deficit. It presents itself as an alternative authority. It offers protection. It dispenses punishment. It creates a parallel world. It replaces state law with violent doctrine. He is correct to insist that Nigerian discontent cannot be addressed without confronting Boko Haram. He is also correct to connect extremism with the broader crisis of legitimacy in the North. He is right to link identity with law. He is right to expose the danger of religious policing in a diverse country.

The Nigerian crisis is deep. It is also layered. It involves poverty. It involves climate pressure in the Lake Chad Basin. It involves ethnic competition. It involves the collapse of education. It involves corruption within the military. It involves political fragmentation. It involves a dangerous mix of fear and apathy. Boko Haram is not the only threat. Banditry has grown. Islamic State West Africa Province has expanded. Rural terrorism has spread across Kaduna, Plateau, Niger, Sokoto, and Zamfara. But Boko Haram remains the symbol of state failure. It is the most enduring insurgency in Nigerian history. Its presence makes every other problem worse. Obadare helps us focus. He forces us to see the core threat. He reminds us that disorder grows when primary threats are ignored.

His recommendations are bold. They deserve scrutiny. They also deserve support. Nigeria needs a coherent security doctrine. It needs clearer international partnerships. It needs to dismantle hybrid religious institutions that contradict its secular constitution. It needs to affirm citizenship. It needs to rebuild trust. It needs to strengthen institutions. The path forward is not simple. But it begins with truth. Obadare speaks that truth. He names the threat. He names the contradictions. He names the urgency.

This is why Dr Obadare’s warning must not be ignored. His arguments bring clarity to a long crisis. They show how Boko Haram feeds on constitutional confusion, state failure, and religious policing. They show how incentives and pressure can force action. They also show how Nigeria must reclaim its secular identity if it hopes to survive as a united republic. I take his warning seriously because I know the seriousness of the man. I knew him before he became a scholar of global reputation. I knew his commitment to the truth when he was still in the newsroom. That commitment has not changed. Nigeria must listen now. The unfinished Nigerian question cannot wait.

Abdul Mahmud, a human rights attorney in Abuja, writes weekly for The Gazette

We have recently deactivated our website's comment provider in favour of other channels of distribution and commentary. We encourage you to join the conversation on our stories via our Facebook, Twitter and other social media pages.

More from Peoples Gazette

Agriculture

FG tasks ECOWAS on leveraging financing strategies for agroecology

The federal government has urged stakeholders in the agriculture and finance sectors in the West Africa region to leverage financing strategies to enhance agroecology practices

Politics

Katsina youths pledge to deliver over 2 million votes to Atiku

“Katsina State is Atiku’s political base because it is his second home.”

NationWide

Tinubu unveils security, economic blueprint to harness marine, aquatic resources

Mr Tinubu directed relevant MDAs to review and implement recommendations by the NIPSS comprehensive study on blue economy development.

Showbiz

Fuji icon Wasiu Ayinde submits lineage form for Awujale throne

Ayinde had signified his intention to assume the Awujale stool, in line with Ijebu customary law and the state’s chieftaincy laws.

Diaspora

Canada unveils $1 billion plan to attract top researchers from Nigeria, others

“For decades, Canada has had a brain drain issue, and now we are in a brain gain mode,” said the Canadian industry ministry.

Africa

FG tasks African countries on eradicating sheep, goat plague

Ms Akujobi urged every country to build surveillance systems that were smarter, faster, and more collaborative.

Economy

FG links industrial growth to reliable energy supply

While acknowledging the importance of the national grid, Mr Enoh said alternative energy sources must complement it.

Africa

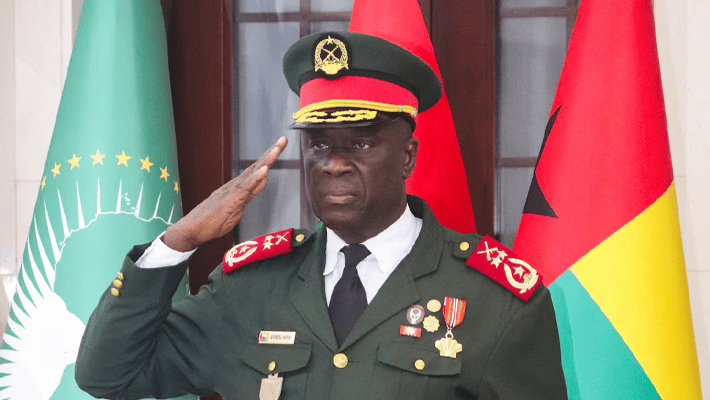

Guinea-Bissau’s transitional military adopts charter barring leaders from elections

Guinea-Bissau has experienced repeated instability since gaining independence in 1974, with only one president ever completing a full term in office.